The Writing of "Frank Sinatra Has a Cold"

Every new art movement has many fathers, some of whom have a more legitimate paternity claim than others. Was it Matisse or Rouault in the ateliers of Paris, or Dufy and Braque from the province of Le Havre, whose pure color and simplification of line pushed aside the old school of Impressionism--and earned the name of Fauvism--or wild beasts? Probably this fine point of art history is still debated in university art departments around the world.

Similarly, there flourished in New York in the 1960s a group of writers whose work became known as The New Journalism and represented a breakaway from the straightforward reporting that daily newspapers fed their readers. This new school borrowed from the techniques of fiction, especially the short story and turned quotes into "dialogue" and background facts into "motivation."

The first to adopt these new techniques is still a subject of debate. Since it never hurts to have a famous father, some point to Norman Mailer, the author of The Naked and the Dead, whose first person account of championship fights and JFK's run for the White House were entertaining and lively. Others trace the new school to more humble origins, pointing to the work of Seymour Krim in obscure journals.

Krim, like Mailer, was a New York writer, a literary critic, who wrote book reviews, in regulation dull prose. As Gay Talese recently said of Lionel Trilling, and others from the Partisan Review: "They didn't write that well. I wouldn't read them for style." But, then Krim suffered a breakdown and underwent shock treatments at Bellevue. He emerged from the ordeal in the early 1950s with a shattered memory and a dazzling new prose style in which he recounted nights spent in Harlem or high on pot in the blacked out city during World War II.

In any event, in short order, the New Journalists had their star, Tom Wolfe, and a house organ, The New York Herald Tribune, which, in an effort to overtake its staid rival, The New York Times, welcomed the off-beat approach to writing. Seymour Krim, in fact, worked on the city desk of the Tribune for awhile as a reporter.

Out of Richmond and W&L, Wolfe was well-mannered and reserved, a guise that served him well in snooping and eavesdropping on the conversations of others, which among the New Journalists became an interview technique.

Wolfe also kept his conservative views well-hidden, and when he landed in New York and began writing, first at the Trib, then Esquire, he found a wondrous group to lampoon--the "liberal merde," he privately called them.

Of all his subjects, including a newly rich art patron who ran a cab company in the Bronx, one was to stand out in the growing New Journalism oeuvre: Leonard Bernstein--the flamboyant Harvard-educated composer--who was known as "Lenny."

The setting for Wolfe's story was a party he crashed at the Bernsteins' Park Avenue penthouse, a gathering to raise bail for a group of Oakland Black Panthers who had been arrested for conspiring to blow up a local police precinct and the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens.

The attendees included old money and new, actors, art dealers, and glamorous couples like the Burdens, Amanda and Carter. They all had one thing in common: political views that Wolfe dubbed "Radical Chic," a phrase that captured the pretensions of an era.

Wolfe's sentences chased each other across the page, poking fun at their subjects along the way. It was a style one admirer, Michael Lewis, described as "rococo," and it had come about by accident.

Out in L.A., doing a story on custom built hot rods, Wolfe had hit a writer's block; and, in desperation, sent his notes to Byron Dobell, his editor at Esquire, hoping he could piece the story together.

Dobell (1927-2017) ran the notes as is, ellipsis and all; and "There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby" set the tone for The New Journalism and overnight made its author famous.

The Bernstein party proved a perfect target, with "The Maestro," dressed in a black turtleneck and a gold chain necklace, saying "I dig" and "I'm hip" to Panther "Field Marshall" Don Cox's riffs on capitalism and revolution, as guests enjoyed "Roquefort cheese morsels rolled into crushed nuts."

When Wolfe's article, "Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's," appeared in New York, a spin-off of the defunct Herald Tribune, Bernstein was widely ridiculed (especially by those who hadn't been invited). Wolfe came in for his share of criticism. "Field Marshall" Cox denounced him as a "bloodsucker"--probably a euphemism; and another partygoer hinted Wolfe was a FBI plant.

Among the congratulatory notes was one from Gay Talese, who signed himself "Don Corleone."

The latter was probably an inside joke from a fellow pioneer who had written on Frank Costello, the real life don, and whose profile of Joe Lewis in Esquire in 1962, Wolfe considered the birth of The New Journalism.

Talese was born in 1932 and grew up in Ocean City, New Jersey, a small town on the Jersey shore that had been founded by Methodist ministers. Talese's father had been born in Italy, and although there were other immigrants in Ocean City, most were Irish who regarded the Italians with hostility and suspicion.

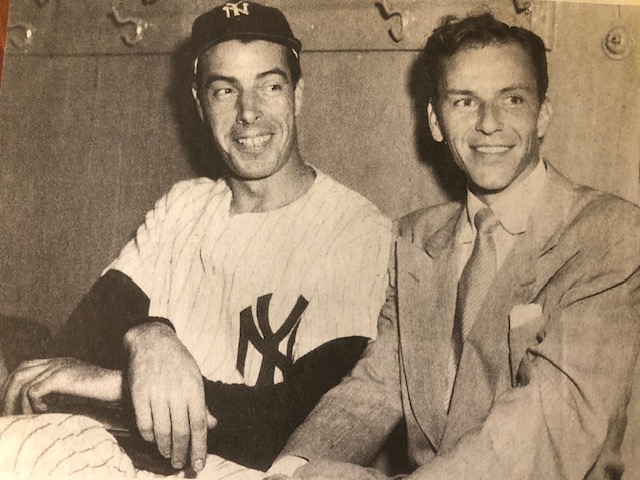

Seeing the world as an outsider proved good training for a journalist. Talese learned to take note of details and gestures that would weave their way into his work, picturing an exhausted Frank Sinatra graciously pause to sign an autograph after losing at the blackjack table, or spying Joe DiMaggio quietly avoid shaking hands with Senator Robert Kennedy at an Old-timers' Day after learning that Kennedy had danced with his ex-wife, Marilyn Monroe, at a Hollywood party.

Talese's father had a tailor shop in which he custom made suits. He was a craftsman who would tear the lining out of a fabric if one stitch displeased him. Gay sometimes helped his father in the shop after school. He was instructed never to interrupt a client, training that turned him into a good listener when he turned to reporting.

Talese dreamed of someday writing for a great metropolitan daily and fell in the habit of taking notes on his fathers' conversations with clients, one of whom was a former New York Times editor named Garet Garrett. The former newsman enjoyed reminiscing about his old boss, Adolph Ochs, the German-Jewish patriarch who ran the paper. His curiosity piqued, young Gay researched in the local library, and wrote an English term paper on Ochs, later recalling it as the "genesis" of the book, The Kingdom and the Power, he was to write on The Times in 1969.

Throughout high school, and in his early years on the sports desk of The Times, Talese devoured a diet of short stories, reading Hemingway on bull fighting, Fitzgerald, Carson McCullers, and the story that moved him most, Irwin Shaw's "The Eighty Yard Run," about a college athlete and his moment of glory. It was these writers--and others--from whom Talese learned to set a scene, use internal monologues, create a mood-building, blocks upon which he would structure The New Journalism.

Aspiring journalists are not always the best students. It is the world outside the classroom that attracts their attention. Even Adolph Ochs, Talese learned, had been an average student in his native Knoxville, a thought that comforted Talese whose report cards were sprinkled with C's and D's.

In 1949, Talese enrolled in the University of Alabama at the suggestion of the family doctor who had studied there. On the train south, he read Irwin Shaw's war novel, The Young Lions, and arrived on campus to study journalism. To the faculty, some of whom had been trained on the old Kansas City Star, reporting was a straightforward affair, but, as sports columnist for the student paper, Talese tried to slip in "some narrative techniques learned from fiction."

Armed with his clips, Talese applied for a job at The New York Times following his graduation. He was hired by Turner Catledge, the Mississippi born general manager, whose nephew was a classmate, and began as a copyboy in the fall of 1953.

It was the end of the Linotype era, and the noisy presses were just below the city room. Talese's job was to ferry the copy between the typesetters and copy editors who trimmed and tightened it, often to the displeasure of reporters whose pride of authorship fell on the cutting room floor.

Faster than you could say "Sammy Glick," Talese was pitching his bosses with story ideas and earned his first big by-line, an interview with a forgotten silent screen star who had worked with Valentino and whom the earnest young copyboy tracked down in a fleabag Broadway hotel.

After a stint with Uncle Sam, it was back at The Times, promoted by Catledge to the sports desk, a section of the paper whose reporters were allowed a bit more freedom. This allowed the stuffy Times to compete with the other New York dallies whose sports writers included the great Jimmy Cannon of the New York Journal-American and Paul Gallico, a Daily News reporter whose first-person accounts of competing with great athletes was later co-opted by George Plimpton, a well-connected young writer who rode the technique to fame as a New Journalist.

New York was a city of "eccentrics" for a young reporter to write about, and neighborhoods to explore, and, after a turn as a sports writer, Talese was a general assignment reporter--specializing in stories of "non-newsworthy people," doormen, bootblacks, clerks who sat in subway booths, watching the lives of the city go by.

It was these "nobodies," the young reporter realized, who often knew what was happening, and when Talese came to write of Frank Costello, he talked not only to the gambler's lawyer but also to his doorman whose eyes had seen everything around them.

Back in the 1950s, big city newsrooms were still solid training grounds, whose seasoned reporters and editors could be generous with their wisdom.

Under Turner Catledge, young reporters learned that "accuracy was kin to religion," and it was James Reston, the Washington columnist, whose "reoccurring advise" to fellow journalists out for a story was "talk to the unhappy ones."

When Talese wrote his portrait of Frank Sinatra, he kept this dictum in mind--seeking out Dick Bakalyan--an actor once in the singer's inner circle who had mysteriously fallen out of favor (which in Frank's world was fairly easy to do).

After seven years, Talese wanted to write more expansive stories than permitted in the news columns and had grown weary of trying to slip his copy by the paper's assistant managing editor, a tyrannical man named Bernstein, who believed that what wasn't taught at the Columbia University School of Journalism didn't belong in the newsroom.

It was Harold Hayes of Esquire who offered Talese a smooth exit with a guarantee of several assignments his first year. Talese was anxious to begin a profile of a former Times colleague, but Hayes persuaded him to undertake a long piece on Frank Sinatra.

Talese was wary: he knew the singer's reputation as a moody and difficult subject, one who harbored deep resentment at a press that he felt had written him off after the golden Tommy Dorsey years when he spun out ballads like "I'll Never Smile Again" before his voice had become thin and gravely; and who seemed washed-up as an actor, until he staged a remarkable comeback in 1954 with his performance as Private Maggio in From Here to Eternity.

Back on top by the early sixties, Sinatra became the "Chairman of the Board," with his entertainment empire and his mature voice that found a new audience with men--and women--who, like him, had known their ups-and-downs over the years.

In exchange for a cover story, Sinatra's publicity people had promised Esquire unusual access, including a personal interview. Even before he landed in L.A., Talese sensed that something was amiss. There were newspaper stories that Sinatra was threatening to sue CBS because a forthcoming documentary suggested that the entertainer was "on friendly terms" with members of organized crime.

Talese was not looking forward to a meeting with Sinatra's publicity team to lay down ground rules. He had been stuck in L.A. before without a story when Natalie Wood had failed to show for an interview and was now worried that Sinatra might torpedo the project.

Luck, it turned out, played as much a part in shaping The New Journalism as it had in the old. After all, if the U.S.S. Maine had not blown up in San Juan Harbor, Hearst would not have won his circulation war.

And so, it was that his first night in town, Talese accepted an invitation to join two friends at a fashionable Beverly Hills club, the Daisy, and no sooner than Talese walked in the club than he spied, at the end of the bar, Frank Sinatra drinking bourbon and surrounded by friends.

Talese was too smooth to approach Sinatra and introduce himself. Instead, he dropped back in the shadows and waited. As Tom Wolfe was to often note, if a journalist was patient, the story would develop before him.

Two of Sinatra's closest friends, Brad Dexter, a character actor, and Leo Durocher, the brash former Dodger manager, stood nearby, but Frank said nothing to them. He was in one of his moods, sullen and quiet.

There was a woman, of course, Mia Farrow, a new girlfriend, the daughter of one of Frank's contemporaries, Maureen O'Sullivan, but the flighty twenty year old was nowhere in sight.

And so, one of the most famous men in the world stood alone at the bar, drinking quietly--and fighting a cold. In the background, the soft rock music that couples had been dancing to, suddenly stopped.

In another room, a stereo came on, and Talese heard a ballad Sinatra had recorded a decade before, "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning." It was a Sinatra classic, one he had recorded when he was still carrying the torch for Ava Gardner, who had left him to suffer his private humiliation in public.

It was this moment, and others, that Talese would capture--an idol, greeting the early morning in a bar, listening to the song that had moved so many other men in dimly lighted saloons, in Chicago and Detroit, over the decades.

Tom Wolfe took notes in shorthand. At the Bernstein party, he had sat in a folding chair with his stenographer notebook transcribing conversations he had overheard. Talese rarely took notes in front of a subject. He would carry index cards cut from shirtboards that he would stuff in his jacket pocket and sneak off to jot down notes whenever he found a chance. As he watched Sinatra standing at the bar, Talese had "thoughts buzzing in my head that I wanted to write down," and he headed towards the men's room to write them down before he forgot them.

Years later, Talese would admit that when he returned to the bar he found that Sinatra had gone into the next room to watch Durocher shoot pool and that the had missed the first minutes of what became an important moment in his profile; he pieced them together from interviews, using what Tom Wolfe called "hearsay," a technique Wolfe had employed in his Bernstein profile in describing a party that Amanda and Carter Burden had given but which he had not attended.

A group had already crowded around Durocher who was shooting against two young players, "very California cool," Talese would describe them; and, he knew enough of Sinatra to know "they were not his style."

The old journalists would read the clips on a subject and borrow from here and there. The New Journalists would, too. Later, Tom Wolfe and Talese would go over the Sinatra profile and annotate where a particular anecdote had come from.

So, Talese was aware of all the stories. How, in an "unexpected moment between darkness and dawn," the singer's mood might shift. Then, his Sicilian temper would flare, there would be a brawl at the Polo Lounge, someone hit on the head with a telephone, and Mickey Rudin, the entertainer's trusted lawyer, would be left to settle the matter out of court.

As usual, Sinatra was impeccably dressed, in an Oxford-gray suit with a vest. His shoes were British and smartly shined. Those around him always wore a coat and tie. It was a sign of respect owed Il Padrone.

In the poolroom, one of the players had drawn the singer's attention. He was wearing funky eyeglasses, a shaggy sweater, and deerstalker boots. He was a science fiction writer named Harlan Ellison who had co-written the screenplay for a film called The Oscar.

In a recent interview, Talese said that he is "not connected spiritually, or in any other way, with the internet," and "doesn't read on-line articles"; but, for those who are so inclined, there today on YouTube is Harlan Ellison's version of the incident. He recalled that Sinatra was "bagged" and that, as Talese wrote, started needling him about his boots. It was "dead quiet," Ellison noted. "Nobody wanted to be near me."

Ellison tried to ignore the singer's comments, until one of Sinatra's cronies reminded him: "Mr. Sinatra is talking to you."

That remark was not in Talese's account, but both recall the following exchange:

"What do you do?" Sinatra wanted to know.

Ellison told him, "I'm a plumber."

Jimmy Bowen, a singer who had once appeared on Sinatra's short-lived televison show, jumped in:

"No, he's not. He wrote The Oscar."

The film featured many of Sinatra's friends, including Tony Bennett and Ernest Borgnine, and Frank himself had a cameo role. It was a coincidence right out of a short story but one that, for some reason, Talese left out; his version of the encounter reads:

"Oh, yeah," Sinatra said, "well I've seen it, and it's a piece of crap."

"That's strange," Ellison said, "because they haven't even released it yet."

"Well, I've seen it," Sinatra repeated, "and it's a piece of crap."

Harlan was 5'5'' but had a brash streak and outsized ego; lawsuits and altercations were to be a hallmark of his career. National magazines like Esquire had not yet embraced the freedom that was to come, and his recollection may be the unsanitized version of the showdown.

"You're in it," Ellison recalled saying. "It takes shit to know shit. You're shit in shit."

By now, word had spread throughout the club of the confrontation. Talese later learned that the manager had heard about the brewing storm, "quickly gone out the door," and had driven home.

Dexter told Ellison it was time to leave, but Sinatra stopped him. Ellison remembered a rowdy exchange with the burly actor, then the club's owner, Jack Hanson, appeared and told the screenwriter to go.

Talese followed him outside. He felt he "had to speak to Ellison" to find out what he was "feeling" during the encounter. This was a technique Tom Wolfe called getting "inside of somebody else's mind," one that he had first used in his story on Phil Specter, the eccentric rock producer. To Talese, it was a way of creating "an internal monologue," as he recalled in a recent interview.

Outside, the reporter made an appointment to speak with Ellison. It was a way, Talese told American Legends, of bringing a subject "into a partnership," an opportunity to ask: "What did you mean when you said" ? And a chance to "go back and re-interview, improve upon a quote."

Back in his hotel, he jotted notes and began "creating scenes as if I were a short-story writer, while at the same time reminding myself that I was a reporter striving for accuracy."

When published, the story made Ellison a minor celebrity and helped propel his successful writing career. In his 2018 interview, he recalled that he "loved" Talese and regarded him as one of the "great gods of journalism."

Over the next few weeks, Sinatra's publicity people put off granting an interview. Frank was "nursing a cold," the reporter was told and had left for Palm Springs, but the truth came out: The entertainer's lawyer wanted to "review" any story to ensure there was no reference to organized crime.

Such a concession was out of the question, though while the matter of an interview was up in the air, Talese was allowed to attend a recording session at which Sinatra was taping a television special entitled Sinatra--A Man and His Music. He also tried to interview on the sly anyone in the singer's entourage who would talk to him, which was always a tricky proposition for Frank's friends. In fact, years later, Mickey Rudin landed in hot water with his boss for (allegedly) agreeing to arrange a Sinatra interview with a biographer the singer detested.

Talese managed to interview Ed Pucci, Sinatra's bodyguard, an ex-NFL lineman, who was hoping for a plug for his new restaurant, and even met with Nancy Sinatra, Frank's talented daughter, whose home phone number he obtained from Sally Hanson, co-owner of the Daisy. Over lunch, Nancy talked openly about her father; he was a "perfectionist," she told Talese and was "...always on time...orderly, and remembers everything."

Nancy was her father's favorite of his three children. When she was a child, he had recorded one of his signature songs, "Nancy (With the Laughing Face)" and had dedicated it to her. In his article, Talese paraphrased their conversations, an indication that even Nancy did not want to chance being quoted directly.

Still determined to interview the singer, Talese asked Floyd Patterson, the prizefighter, to put in a good word for him. Talese had profiled Patterson for Esquire and knew Sinatra admired him. This also proved a dead end.

In a recent interview, Talese called his approach to reporting "the art of hanging out." "We would take walks together, go to dinner, they would meet my wife," Nan, a well-known book editor, he said of his subjects. With Sinatra, the closest he got was a few brief meetings; each time, the singer brushed off any request for an interview.

In L.A., Nancy even accompanied Talese to the set of Assault on a Queen where Sinatra was shooting a film with Verna Lisi, and his friend, Richard Conte.

Talese saw his opportunity and knelt in front of a chair where the entertainer was relaxing. When he requested an interview, Sinatra politely told him: "I'm sorry, but I just don't have the time," explaining that he was leaving for Mexico after the shooting. It was the last time the journalist saw the singer.

In the end, Talese realized there was no way out of the paradox he had been trapped in: To gain Sinatra's trust, a studio photographer, Dave Sutton, had told him, "You have to be a friend," and a friend "Can't write about him."

Even before his last meeting with Sinatra, Talese kept Harold Hayes up-to-date about the brush-offs he was getting. He wrote the editor: "I may not get the piece we'd hoped for--the Real Frank Sinatra--but perhaps, by not getting it, and by getting rejected constantly and by seeing his flunkies protecting his flanks, we will be getting close to the truth about the man."

Getting closer to that "truth" meant seeking out the "nobodies," as he had done at The Times: Johnny Delgado, Sinatra's double, and George Jacobs, his valet with whom the singer could relax, playing cards late into the night--and drinking Jack Daniel's.

Jacobs was a personable African-American who had traveled the world with his boss and was devoted to him. After fourteen years, he, too, was banished overnight when the singer learned that Jacobs had been seen dancing with Mia Farrow at a discotheque on the eve of her divorce from her brief marriage to Sinatra. When Jacobs showed up at Sinatra's house in Palm Springs, he learned that he was fired for his breach of loyalty to the man whose first big hit, "All or Nothing at All," made with Harry James's band in 1939, had become a personal anthem.

As he wrote in his own memoir, Bartleby & Me, Talese knew that he had enough material in "my typed notes" to write his profile. Before leaving for New York, the journalist gave Nancy a note to relay to her father. He told the entertainer that he came as a friend and was leaving as one but that if he had been "allowed to share your informal company...there is no doubt that I would have produced a classic profile on you...."

When published in Esquire in 1966, Talese's article, "Frank Sinatra Has a Cold," did become a "classic," one of the lasting examples of The New Journalism.

Talese never heard from Sinatra. "Frank never got back to me," the journalist told American Legends. "The people you interview never get back to you. Sometimes you hear from their lawyer, but I've never been sued." He added: "I never do hatchet jobs," and that he had interviewed "gangsters, pornographers," but "I kind of respect them" and find "some redeeming aspect in their personality. If I don't respect them, why write? Writing is too hard."

Endnotes: Ron Martinetti for AL. Ron is working on a long essay, "Hutchins at Chicago." He would like to thank Gay Talese for talking to him by telephone, thereby waiving one of the journalist's rules to avoid telephone interviews( along with tape recorders: "It's just Q & A," is the way he puts it, "The writer has no voice"). Unless otherwise indicated, Talese's quotations were drawn from his two memoirs: A Writer's Life (Alfred A. Knopf, 2006) and Bartleby & Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener (Mariner Books, 2024). The art history anecdote was cribbed from Werner Haftmann's Painting in the Twentieth Century (Praeger, 1966) In his essay on The New Journalism, Tom Wolfe credits the origin of the term to the late Pete Hamill who was preparing an article on Talese for Seymour Krim's Nugget.

The article never appeared, but the term endured. The essay is a preface to Wolfe's (and E.W. Johnson's) anthology, The New Journalism (Harper & Row, 1973) Among the practitioners gathered by Wolfe were Esquire alumni Brock Brower, Terry Southern, "and, above all, Gay Talese." Talese returned the compliment. In talking to American Legends, he referred to Wolfe, who died in 2018 at 88, as a "great figure, you can't imitate him"; and noted that there was "no competition" among the New Journalists, as plagued the fiction writers of the same generation: Mailer, Styron, and Roth (whom he regarded as "stuck on himself"). An earlier journalist Talese admired was Joseph Mitchell who wrote for The New Yorker in the 1940s. After discovering Balzac in the 1970s, Tom Wolfe decided to turn to fiction, finally publishing his novel of New York, Bonfire of the Vanities in 1986. A selection of Jimmy Cannon's columns was collected in Nobody Asked Me, But..." (ed. by J. Cannon and T. Cannon, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1978) Cannon's work was another tributary that flowed into The New Journalism, influencing the writing of Pete Hamill (1935-2020) and Jimmy Breslin (1928-2017). "Nancy" was written by Jimmy Van Heusen and Phil Silvers; a close Sinatra friend, Van Heusen also wrote (with Sammy Cahn) "All the Way," another signature tune. The George Jacob's anecdote was taken from Kitty Kelley's (unauthorized) Sinatra biography, His Way (Bantam Books, 1986) Despite their bitter parting, Jacobs published an engaging memoir of his mentor: Mr. S: My Life with Frank Sinatra (HarperCollins, 2003) Sinatra abhorred Kelley's book which probed his relationship with Sam Giancana, the Chicago gangster. Concern over questions of that friendship was one of the reasons the entertainer's publicity people avoided an interview with Talese. Sinatra died in Palm Springs in 1998, to the end, doing things, like the song says, "My Way." After this article was posted, Talese, always a journalist's jounralist, sent AL a note thanking it for "an excellent" job.