![]()

|

Kerouac: Homage To Jack |

Jean-Louis Kerouac: His life was the stuff of which legends are spun. The son of a printer, he was born in 1922, and grew up in a mill town, Lowell, Massachusetts. The Kerouacs were French- Canadian, descended from fur trappers and traders. Even as a boy, Kerouac knew what he would be: a writer. Athletic, rugged, handsome, he called himself Jack--after Jack London, and, like London, his vision of the world was romantic and adventurous.

Yet, Kerouac might have remained in Lowell, another kid who dreamed of glory, if luck had not lent a magical hand. In high school, Kerouac was spotted playing football by an Ivy League scout and was recruited to play in the backfield for Columbia University.

The university arranged for a scholarship, and Kerouac arrived on the Morningside Heights campus in the fall of 1940. Like some character in Balzac, another writer he admired, the glittering prewar city lay before him, with all the promise it held for youth.

But the world has a way of holding out its treasures-- only to snatch them away. Freshman year, Kerouac was injured in a game and sat out the season. According to a biographer, sophomore year, Jack quit the team and dropped out of Columbia because the coach kept him on the bench. (Ann Charters, Jack Kerouac, San Francisco: Straight Arrow, 1973)

America was at war, and Jack joined the Navy. In boot camp, however, he was unable to take the discipline. One day Kerouac dropped his rifle and walked off the drill field. He was confined to a Navy hospital where he told the psychiatrists he was writing a novel entitled, The Sea Is My Brother. The aspiring author was given an honorable discharge, with an "indifferent character."

Kerouac returned to New York and lived with an old girlfriend, Edie Parker, who was studying art at Columbia. Edie was zany--a free spirit-- and their West End apartment was filled with her strange friends. Through Edie, Jack met William Burroughs, a jaded dilettante and morphine addict, and Allen Ginsberg, then a young poet, obsessed by Blakean visions, who had been expelled from Columbia for writing obscenities on his dormitory window. (Years later, in Tangiers, Kerouac and Ginsberg assembled Burroughs's notes on his drug addiction into a book whose title Kerouac suggested: Naked Lunch.)

Kerouac worked at odd jobs and occasionally shipped out as a merchant seaman. In 1946 he began a novel, The Town and the City. Written in the style of Thomas Wolfe, the book fictionalized Jack's boyhood in Lowell and the new world he had discovered around Times Square and Greenwich Village. He wrote about hustlers, disillusioned intellectuals, junkies. "The only ones for me are the mad ones," Kerouac would later write. Using a phrase coined on the streets, he called them "beat"--a term that later epitomized a postwar generation.

In 1949, at the suggestion of Mark Van Doren, Jack's Columbia English teacher, Harcourt, Brace accepted The Town and the City for publication. While he awaited the book's release, Kerouac dreamed of buying a ranch with his future royalties and inviting his friend, Neal Cassady, to live with their families on a commune.

Cassady was a manic, wild character who had blown into New York from Denver a few years before. As a youth, he had been in and out of reform schools for joy riding. Life--to Neal--was "pleasure and kicks:" Cars, Tea, Sex. Ginsberg was in love with him; Kerouac described him as "...a young Gene Autry--trim, thin-hipped, blue-eyed, with a real Oklahoma accent--a sideburned hero of the snowy West."

The Town and the City did not bring Jack the fame he had hoped for. But he was already at work on a new book, based on what he called "my life on the road." Jack had hitchhiked to Denver to see Neal and had stumbled in alleyways and poolhalls following his friend through "the sadness and joy" of his own dark world.

But through Neal, Jack had found his theme and his voice. "We gotta go and never stop going till we get there," Cassady had said. When Jack asked where they were going, Neal replied, "I don't know, but we gotta go till we get there." It was Neal's frantic speech and letters--with their echoes of jazz and bop-- that led Jack to create what he called "spontaneous prose."

In the spring of 1951, Jack Kerouac sat at his typewriter and wrote, On the Road. He completed the book in three weeks, typing it on a roll of teletype paper. As soon as he finished, he informed Neal: The story "deals with you and me and the road...Went fast because road is fast." (Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters, New York: Viking, 1995)

Jack was pleased by his triumph and proud of the departure he had made from "previous American Lit." "I really wrote a great book," he assured Cassady in one letter; in another he promised: "I won't get the screwing Melville got"--referring to the great 19th century writer who had labored through life in obscurity.

But Kerouac's dreams were soon shattered. "I am completely f---ed," he told Neal after two publishers had turned down the novel in quick succession. Jack's own publisher found the work too "new and unusual," and doubted a book "about bums" would appeal to the public.

Following his failure to sell his novel, Kerouac traveled to Mexico City to see Burroughs.

There Jack wrote poetry, later published as Mexico City Blues, experimented with drugs,

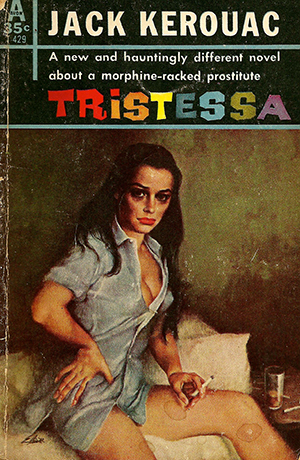

and fell in love with a Mexican prostitute--a doomed affair he wrote about in Tristessa.

(The book was published in 1960 as a paperback original since even after he became

famous, the publishing Establishment treated Jack as a second class writer.)

Tristessa was a morphine addict; Kerouac got high with her. The book was a long,

hazy prose poem in which Jack wrote of her "long sad eyelids" and "Virgin Mary

resignation." A rooster screamed under the bed in her pitiful adobe. Jack saw himself

as "wild haired" and "mad" riding in taxi cabs with his love through the wet

city streets. "Why are you so sad?" Tristessa would ask him. These were

angry, bitter years for Kerouac--a time of rejection and despair.

Then, in 1954, On the Road landed on the desk of an editor at Viking named Malcolm Cowley. A well-respected scholar, Cowley had written a book on American writers in Paris, and he recognized the breakthrough Kerouac had achieved in language and style.

At Cowley's suggestion, Kerouac edited the manuscript to make it more palatable to Viking. According to John Montgomery, the text was cut in half. Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Cassady were given pseudonyms to disguise their identities. Kerouac also removed a number of passages, including one involving Neal's interest in a pre-teenage girl. When the publisher remained nervous, Cowley assured them that Kerouac's friends were "not the type of people who sue."

When finally published in 1957, On the Road was an immediate success. In The New York Times Gilbert Millstein hailed the book as an "historic occasion" and praised its "beauty" and "technical virtuosity." Overnight, Jack Kerouac found himself famous--dubbed by the popular press as "King of the Beats."

It was a supreme irony that Jack would be regarded as a radical--"a know-nothing Bohemian" one critic called him--though his book was a joyous ode to late 1940s USA with its raw beauty and wild freedom symbolized by the open road; and the characters--American characters--cowboys, farmers, panhandlers--Jack met along the way.

But success proved a trap for Kerouac. Instead of growing as an artist, he reworked the same themes, convincing himself he was creating a Proustian legend about Neal and his friends. The Dharma Bums (1958) dealt with the West Coast Beats; Visions of Cody (1960) was another paean to Cassady based upon taped conversations in which Neal expounded upon his girls, cars, and travels. (As Ann Charters noted, Jack's books neglected to mention "the men in Neal's life.")

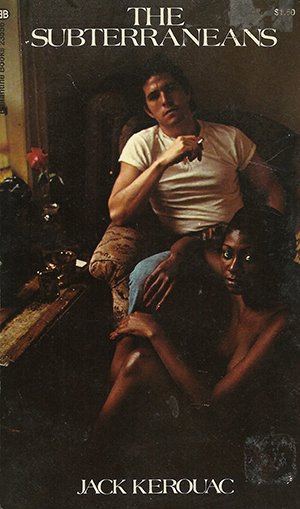

Among the warmed over versions of On the Road, Jack managed to spin out (on bennies to be sure) The Subterraneans, the story of his affair with a lithe black beauty, Mardou Fox. "The rainy night blooping all over, kissing everywhere men women and cities in one wash of sad poetry" Jack began a riff on Mardou and maybe their love, " She squats on the fence, the thin drizzle making beads on her brown shoulders, stars in her hair...."

The novel was originally set in Greenwich Village but was changed to San Francisco to mollify publishers who again feared libel from Jack's real life friends--Ginsberg, Corso, Stanley Gould, a local hipster who was always high -- all of whom appear thinly disguised in the book. Jack's magical prose perfectly captured the smoky nights listening to Charlie Parker and talk filled dawns of the "urban Thoreaus" whom Ginsberg dubbed the "subterraneans": Those who "are intellectual as hell and know all about Pound without being pretentious."

Jack was of another world with his lumberjack shirt and drinking bouts in seedy bars. There was one occasion when he, Allen Ginsberg and David Amram, a jazz musician, spent the evening at Allen's apartment drinking and reciting poems with Buddy the Wino, a Bowery bum they picked up off the street. While Buddy was digging a poem Allen read, Jack turned to Amram and said "real quietly:" "These guys are where I get so much inspiration from and learn so much from. They are the true poets of the streets." (B. Gifford and L. Lee, Jack's Book, St. Martin's Press, 1978)

The 1960s should have been Jack Kerouac's decade. His books were widely read on college campuses. Young people imitated him, hitchhiking around the country. But Kerouac turned his back on the flower children he had spawned. "It's politics, not art anymore," he complained.

Moreover, Jack had become reclusive. After years of struggle, he had finally crossed his "ocean of suffering" but had not found happiness on the other side. To the end of his life, Kerouac was ridiculed by the press and attacked by jealous rivals. In a famous TV interview, Truman Capote dismissed Jack's work as "typing" not writing. Stung by such comments, Kerouac turned further away from the world. He lived with his invalid mother--the memere of his novels--in Florida, trying to repay her for the years she had worked in a factory to support him. Jack's days were spent drinking beer and brandy, listening to jazz on his hi-fi. Once, in a rare public appearance, he dumbfounded his young admirers by expressing support for the Vietnam War.

Despite his growing popularity, Jack's books enjoyed modest sales and money was often tight for him and Memere. He did not drive a car and there was no telephone in the house. Shortly before his death, Jack complained to Carl Adkins, one of his St. Petersburg pool hall buddies: "All the rich kids buy J.D. Salinger in hardback, and what do I get? Bums like you buy one paperback for half a buck and then let ten of your friends read it." (The Kerouac We Knew, ed. by John Montgomery, Fels & Firm Press, 1987) Later, Adkins recalled that someone referred to Jack's time in Florida as "the melancholy years." "He wanted to take the pain out of the world," poet Jack Micheline later said. "No one can do that."

Jack remained deeply religious, as he was throughout his life. He combined a mystical Catholicism with--again according to Adkins--"the tenets of Buddhism." Whenever Jack heard someone knock religion, he would say, "Ah, Jesus died for bums like you."

Jack grew estranged from Neal who was involved in the counterculture as a member of the "Merry Pranksters," a group who drove around San Francisco in a bus painted in psychedelic colors. When Neal died of a drug overdose in Mexico, he and Jack had not seen each other for almost five years.

Finally, in 1969, the end came for Kerouac. After a night of heavy drinking, he hemorrhaged and was rushed to the hospital where he died at age 46. He was buried in the local Catholic cemetery in Lowell, the city he had left as a boy, filled with those dreams that took him on the road.

Ron Martinetti for AL.